Biography

Born in 1933 in London, England, into a family of physicians and scientists (his mother was a surgeon and his father a general practitioner), Oliver Sacks earned his medical degree at Oxford University, followed by residencies and fellowship work at Mt. Zion Hospital in San Francisco and at UCLA in the early 1960s. In 1965, he moved to New York City, where he practiced neurology until his death in 2015.

In 1966 Sacks began working at a chronic care hospital where he encountered an extraordinary group of patients, many of whom had spent decades in strange, frozen states, like human statues, unable to initiate movement. He recognized these patients as survivors of the great pandemic of sleepy sickness that had swept the world from 1916 to 1927, and treated them with a then-experimental drug, L-dopa, enabling them to come back to life. They became the subjects of his book Awakenings, which later inspired a play by Harold Pinter (“A Kind of Alaska”) and the 1990 Oscar-nominated feature film (“Awakenings”) with Robert De Niro and Robin Williams.

His approach was not to fit the patient into a syndrome or disease, but to examine the ways in which an individual coped and adapted in unique ways to different neurological challenges. He recognized every human being as an individual with their own strengths and dignity, their own ways of experiencing the world. He wrote about hitherto unknown or misunderstood conditions such as Tourette’s syndrome, aphasia, and autism, and in this way was the godfather of what came to be called neurodiversity.

Sacks is best known for his books of case histories such as The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Musicophilia, and An Anthropologist on Mars, in which he describes patients struggling to live with conditions ranging from Tourette’s syndrome to autism, parkinsonism, musical hallucinations, epilepsy, phantom limb syndrome, schizophrenia, retardation, and Alzheimer’s disease. He investigated the world of Deaf people and sign language in Seeing Voices, and a rare community of colorblind people in The Island of the Colorblind. His autobiographical Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood was published in 2001, and at the end of his life he published a final autobiography, On the Move.

Sacks’s work regularly appeared in the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books, as well as various medical journals. The New York Times referred to him as “the poet laureate of medicine.” Although his medical colleagues at first dismissed his work as being not quantitative enough, his emphasis on humanity and the individual stories of patients eventually became widely influential, even in medical education.

During the last decade of his life, Dr. Sacks served as a Professor of Neurology and Psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center, and he was also designated the university’s first Columbia University Artist. He was also a professor of neurology at the NYU School of Medicine and a visiting professor at the University of Warwick.

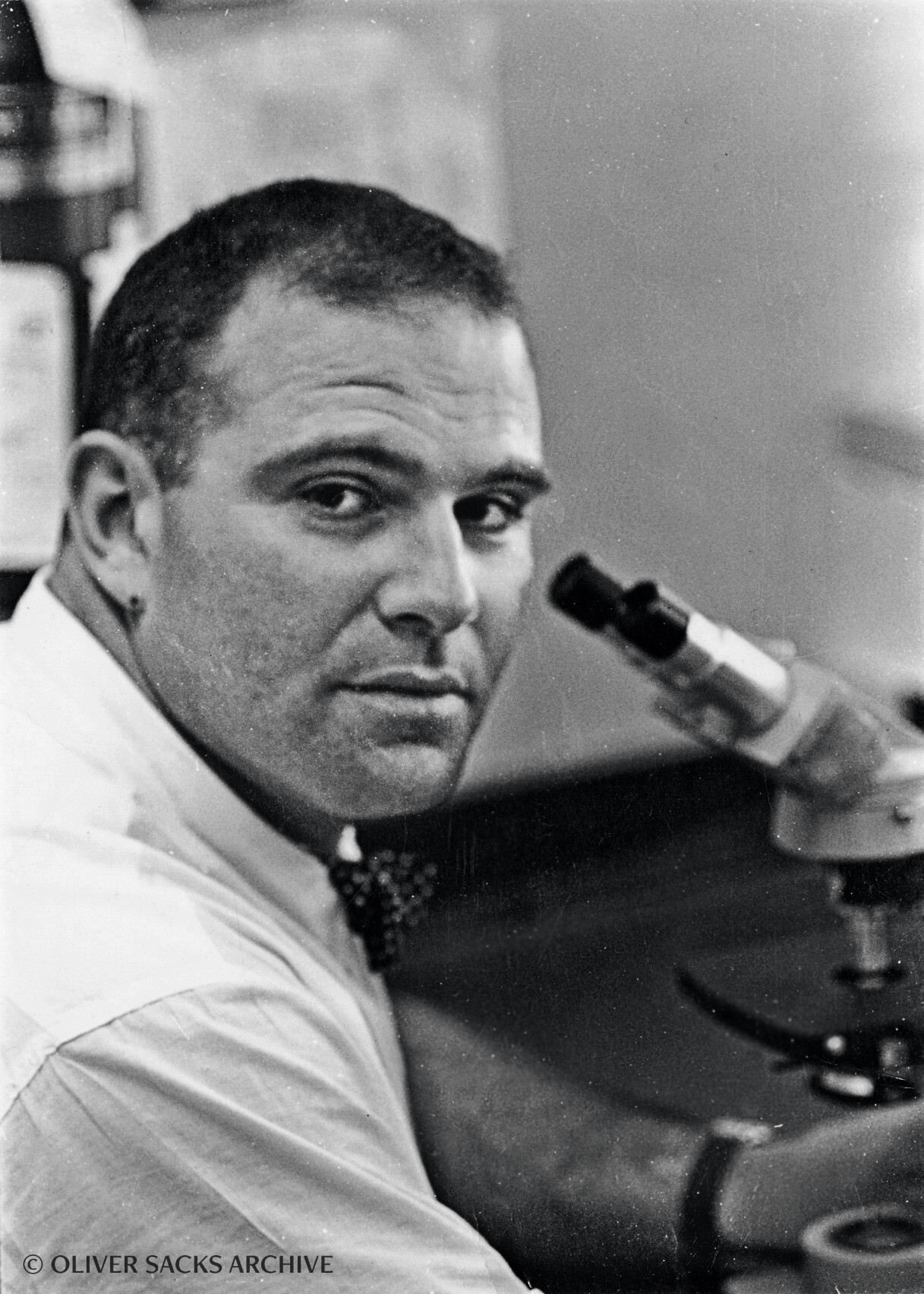

Photos by Bill Hayes, Lowell Handler and The Oliver Sacks Archive:

Testimonials

“His writing showed me ... there’s truth and there’s knowledge, and there are important things about the human experience that you just don’t get from medical textbooks. And there were truths to be found, in going deeply into people’s lives and seeing what happens to them and how it unfolds over time. Arguably Oliver Sacks is the most important person for me in shaping my idea of what a doctor should be, about what a good doctor is.”

“He was asking as hard as a person can, “WHO ARE YOU? I NEED TO KNOW. I NEED TO KNOW MORE – I NEED TO KNOW EVEN MORE.” And his attention would release people. He could get secrets, he could learn things. And what I realized is he will tell stories about people in terrible trouble – who are brave, and special, and full of heart – paralyzed but not over – And he will take this thread of them, and he will pull them out, pull them slowly out. But what he also did simultaneously, which was the great part, is he pulled the whole world in the other way. He would tell these stories so well that other people – playwrights, actors, poets – would pick up the stories he tells – retell them or tell them in their own way.”

“Oliver invited people to look at themselves—and people, when they’re looking at people with disabilities, they’re also looking at themselves. And they’re afraid to look in the mirror. People [sometimes] think he was saying, LOOK AT THE OTHERS. He’s not saying that. He’s saying, LOOK AT US ... AS A WHOLE HUMAN RACE.”